The Time Is Now — Tinnitus Sufferers Take the Lead in Research

By Hazel Goedhart, Director of Tinnitus Hub

It was the moment I had been working towards for years; presenting at the Tinnitus Research Initiative (TRI) conference in Dublin last June. But it did not go as expected…

I had not been nervous beforehand, excited rather. It was the first time that we got a speaking slot at the biggest tinnitus research conference – maybe even one of the first times that any patient organization got to speak at TRI. I was happy at the opportunity to represent the voices of tinnitus sufferers in front of hundreds of tinnitus researchers. I was well prepared. In my day job (for a financial services company) I lead dozens of people and give presentations all the time. I am not only comfortable and confident giving public talks, but I even enjoy it. What could possibly go wrong?

My confidence dwindled however as I got up on stage. For a conference with hundreds of participants, the huge auditorium seemed suspiciously underpopulated; I could spot at most fifty people in the audience. Was no one interested in my talk?

I resented the fact that I had been scheduled as the very last speaker of the last session on the last day. Some people might have already left for home, and most of the remaining folks were, I assume, attending the other session held in parallel to mine. The theme of my session was patient involvement, but the scheduling made it clear that this topic was not considered a high priority. I tried to shake off the feeling of pointlessness. I simply had to get up there and deliver our message with gusto. Yet my mouth felt as dry as the Sahara Desert, and I forgot to bring a drink on stage. Too late now…

If you would like to see me sweat, you can find the full recording of my talk below. Or you can view the slide deck (minus publicly embarrassing video evidence, haha). For the geeks amongst you, you can even explore the full dataset that my talk was based on. But let me take you through my key messages right here.

If we want to build a bridge between patients and researchers, and more meaningfully involve tinnitus sufferers in research, we first need to fully understand the experiences of tinnitus sufferers. From a survey we conducted among 2,727 people, we know that over 80% of those who see a healthcare professional for their tinnitus get no benefit from this whatsoever. We also know that less than 3% of tinnitus sufferers are satisfied with current treatment options!

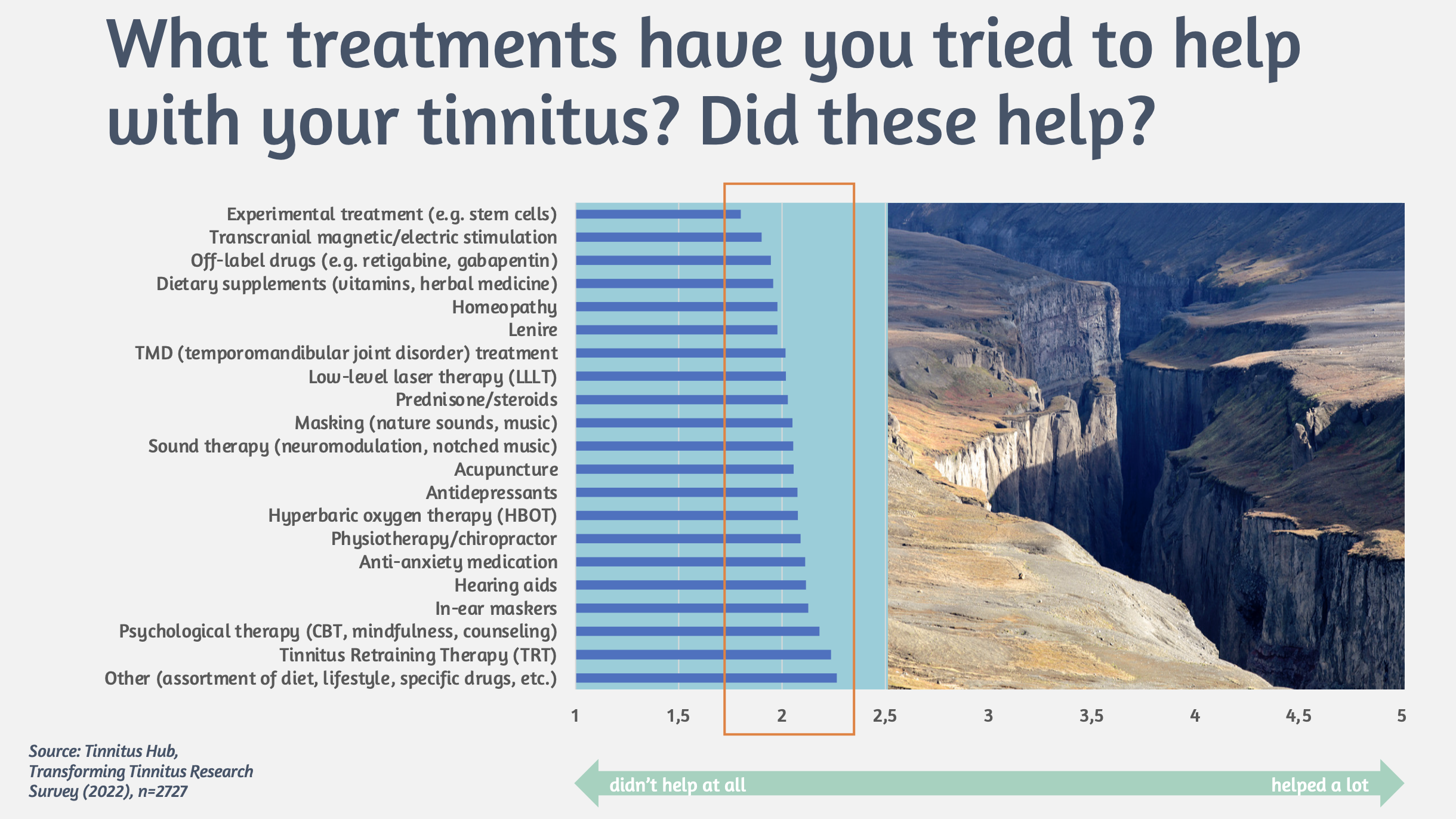

When we look at what treatments people have tried and whether these helped them, the ‘winning’ treatment is an assortment of self-help strategies like lifestyle and diet changes. And no treatment scores higher, on average, than 2.5 on a 5-point satisfaction scale. So, there is a huge chasm between patient expectations and the reality of treatments. Yet, most current tinnitus studies focus on testing and retesting existing treatments like CBT, sound therapy, and transcranial electric/magnetic stimulation.

This is why people turn to places like Tinnitus Talk, where they can engage with others who understand their predicament, learn from each other’s experiences, discuss treatments, and support each other. Much as healthcare professionals like to disparage online support groups as ‘bad’ and ‘negative’, the reality is that 64% of Tinnitus Talk users have reported benefit from it, while only 18% of those who have sought professional care report benefit from that. The numbers speak for themselves.

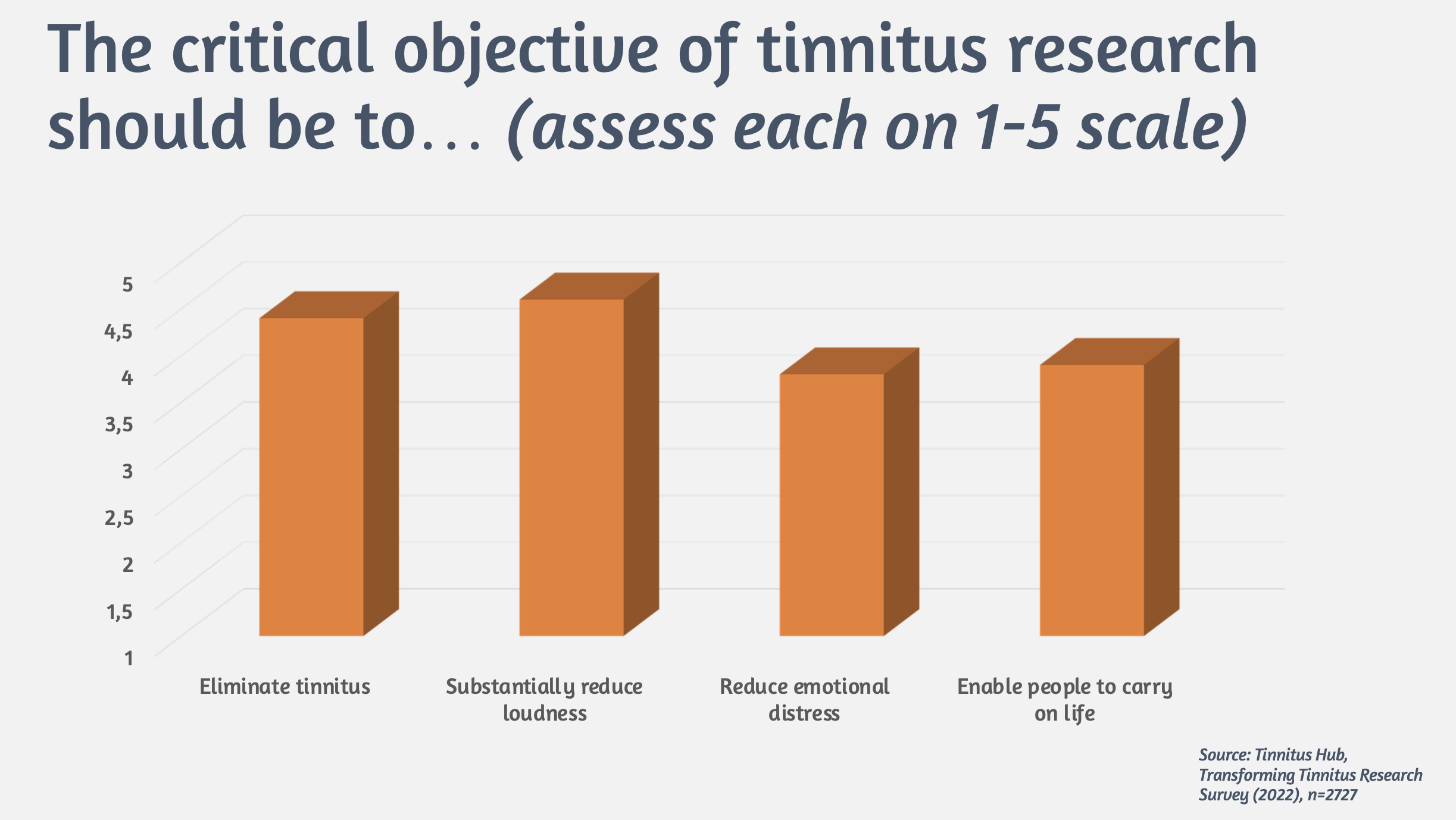

So, if the current treatments don’t help (or maybe only help some people), what does that mean for research? More specifically, what are tinnitus patients expecting from research? We asked them, and the outcomes were rather interesting, and also a bit surprising. We gave respondents four potential objectives for tinnitus research and asked them to rate each one on a scale from 1 (not important) to 5 (very important). As you can see in the graph below, the differences are not huge, but the winner is “substantially reduce tinnitus loudness”, which is rated on average 4.3 out of 5. The surprising part is that “eliminate tinnitus” scores slightly lower, perhaps because people may not consider this a realistic goal? Who knows…

As expected, other objectives related to reducing emotional distress and improving quality of life are considered slightly less important, secondary to reducing the tinnitus signal itself. Not surprisingly then, respondents also indicated that the fields of research considered most important (by a wide margin) are neurology and audiology.

Another way that we assessed what kind of research tinnitus sufferers want is to let them vote on academic papers. We conducted six ‘research roundups’ where we collected all tinnitus studies published in the previous month and asked Tinnitus Talk members to vote for the paper that they found most valuable. Some interesting trends emerged, most notably: 1) the winning papers were all related to treatment efficacy testing for non-psychological treatments; 2) the winning papers always won by a large margin; and 3) runners-up were all meta-analyses or studies into the neural correlates of tinnitus.

[NB: Sources for all the above-mentioned statements are from our own data collection and investigations, detailed references can be found in the slides and links below.]

But there’s more. It is not just about the topics being studied or the goals of research. People also care about how researchers talk about tinnitus and which aspects of tinnitus they focus on. In a very interesting study by Deborah Hall that we co-authored, based on qualitative analysis of online discussions between Tinnitus Talk members, it emerged that sufferers would like to see the diversity of tinnitus experiences recognized, as well as the short-term fluctuations in experience, and the severity of suffering faced by those on the extreme end of the spectrum. All of this calls for a more individualized approach to studying tinnitus, rather than the one-size-fits-all approach that is still quite prevalent.

Ok, so we know that tinnitus patients want research to be aimed at reducing the tinnitus signal rather than approaches that promote coping or habituation. They want to see a more fundamental understanding of the nature of tinnitus. They tend to care more about applied than fundamental research. And finally, they want a more individualized approach. But let’s face it, no clear research agenda can emerge from the patient community alone; this requires engagement with researchers.

It is our strong belief that in order to facilitate patient-researcher engagement, there are a few thorny issues that need to be worked through first. These are issues that, if not debated and resolved, will continue to divide patients and researchers and inhibit meaningful collaboration. The patient input described above hints at some of this, but let me be more explicit – keeping in mind that this is mostly my own interpretation based on hundreds of discussions I have had with tinnitus sufferers (including our Patient Expert Panel) and researchers.

First of all, we need to have a debate about loudness versus distress. Patients clearly want studies to focus on loudness reduction, but many studies are fuzzy or opaque in describing which one is targeted. When asked about this, researchers will often reference data that ‘proves’ distress is not (or only mildly) correlated to tinnitus loudness, and therefore it is the distress that we should truly care about. There are many problems with this argument, starting from the fact that we do not even have a reliable way of measuring loudness. Furthermore, loudness is not the only characteristic patients care about; they also care about the type of tinnitus sounds, how their sounds fluctuate, or how their tinnitus responds to environmental sound, to name but a few. Finally, the lack of correlation between loudness and distress may apply between individuals but that does not make it applicable per se within one individual. In other words, if my tinnitus were to double in volume today it would likely double my distress. So, let’s have an honest conversation about whether research should target loudness or distress. [To be clear, we acknowledge the possibility that there may not be a clear dichotomy between the two, because at the level of the brain the two can interact in complex ways. But if this is the case, researchers should be explicit about such presumptions.]

Secondly, we need to discuss outcome measures. This refers to how success is measured when new treatments are tested in clinical trials. Most trials use either the Tinnitus Functional Index (TFI) or Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) to measure the results of treatment interventions. However, we should beware that these are highly subjective measures that are bound to create a lot of noise in the data. They also leave out a lot of measures that are important to patients like the characteristics of their tinnitus (e.g. how it fluctuates), comorbidities like hyperacusis, and general wellbeing. Perhaps most importantly, the THI and TFI changes that are considered ‘clinically significant’ are in reality of questionable benefit to patients, as they typically correlate with feeling only ‘slightly better’. This leads to studies being touted as a “breakthrough” or even a “cure” in the media because researchers achieved an average TFI reduction of 13 points, which is considered clinically significant. This is hugely misleading for patients and sets the wrong expectations.

Therefore, researchers need to become more transparent about treatment outcomes to avoid breaching patient trust.

Apart from the above hot topics for debate, we also need improvements that enhance the quality of tinnitus studies. For instance:

- Be careful and explicit about patient selection, whom is this treatment for?

- Ensure that the data allows us to draw conclusions about what works for which patient group (sub-typing);

- Agree on the minimum datapoints to be collected in all studies;

- Involve the right competencies in studies, e.g. include biostatisticians;

- When testing treatments, this should always be through randomized controlled trials (RCTs);

- Report details on dropouts and adverse events, which is just as important as reporting success.

The above may seem obvious, but all too often these conditions are not met, leading to many barely useable study results and a waste of time and effort in the eyes of the patient community.

I ended my talk by thanking the many researchers who have collaborated with us and been great ambassadors for patient-driven research. Truly, this gives one hope. But I also gently cautioned the audience that many researchers seem threatened by patient involvement, or even seem to dislike patients having any opinion on research. I illustrated this with a few examples from my own experience. But I won’t mention these here, because as soon as I stepped down from the stage, I experienced another clear example.

As I was still shaking from nerves and dying to water my parched mouth, I was cornered (yes, almost literally) by two senior researchers. I had met them both before, and I knew they were well respected tinnitus researchers in the field of psychology. Psychologists tend to believe that research should focus on reducing tinnitus-related distress and some of them will argue that habituating to one’s tinnitus is effectively a cure. (As someone who is mostly habituated to my tinnitus, I strongly dispute this, but that discussion is for another day.)

These two were angry – and I do mean angry (!) – at our suggestion to prioritize biomedical research, as they believed this would lead to less funding for psychological research. [I do not know much about research funding, but I don’t think it works that way?] They also accused us of collecting ‘biased’ data through our surveys, in the sense that our sample mostly represents those who are struggling. I would argue that that is, in fact, the point. These are exactly the voices that deserve to be heard most in research.

While I am happy to have difficult discussions – we are obviously not perfect, and our viewpoints probably do not represent the entire tinnitus community (if there is such a thing) – I felt patronized. Clearly these guys were not interested in listening to my side, because they already knew they were right. What a sour note to end on.

Luckily, it didn’t quite end there. I later connected with some younger researchers (including a psychologist) who were excited about my talk. They were talking about how they planned engage patients more in their research. I guess all is not lost, and we certainly are not giving up. This is just the beginning. We will be figuring out how to bridge the gap by facilitating discussions between researchers and tinnitus sufferers on the ‘thorny issues’ we identified above. There is a way forward, and we hope you will join us on this journey.

The work referenced in this blog was carried out with support from the Wellcome Trust.

Sources:

Write a Comment